“To reject a child’s language in the school is to reject the child,” Jim Cummins famously stated once (Cummins, 2001, p.19). And that rejection has dire consequences. Students have reported feelings of shame, insecurity, not belonging and futility (Agirdag, 2017) as a result of being punished at school for using their home languages.

Not every school would punish their students for using their home languages, luckily, though it’s been wide-spread practice in Belgium as late as 2017 (Agirdag, 2017). However, it is still common practice in the Netherlands (and elsewhere), to ban them. Stepping into an Amsterdam primary school, you should not be surprised to be greeted by signs proudly exclaiming: “Here we only speak Dutch!” Other schools might be more discrete, and merely put a clause in their school policy, stating the same. And if that weren’t enough, you as a parent might even be told off for speaking your other-than-Dutch-language with your child on the school premises. Yes, in the Netherlands, in 2020. Outlandish as it may sound, such discriminatory practices seem to be based on misguided goodwill. The idea being: “Children need to stop speaking their first languages, in order to master the school language faster”.

However, not only do we know that assumption to be wrong, but its opposite has also been proven again and again.

Children’s home languages are not an obstacle to learning the school language. Rather, multilingualism, when treated correctly, can have a positive effect on students’ performance at school (Cummins, 2009). The research has been there for decades.

And so, I think it’s time we asked ourselves:

- How much longer are we going to wait around for schools to catch up?

- How much longer must we watch on, as our schools continue to fail our multilingual children, labeling them as “students with a language deficit”?

- How much longer can we endure schools’ and policy makers’ complaints about attainment gaps between migrant and non-migrant students, while we know that the solutions are in their hands?

We needn’t wait. I’m inviting you to make a difference, and join our path towards inclusion and equity. Don’t know where to start? Here are 5 free and simple steps you can implement in your school. Starting today.

1, Hang up welcome posters

If you are still reading, that probably means you are dedicated to show that your school welcomes all languages. Nothing is simpler than that! Create welcome posters, using simple words and phrases, such as ‘Hello!’ ‘Welcome!’ or ‘How are you?’. Make sure all languages and dialects are represented, and that the poster does not confirm harmful status differences between languages. Such posters will immediately send out the signal that all your students (and parents) are part of the school community. It won’t cost you any time, either. Students and parents will be more than happy to make the poster for you.

On the photo: Pepita Franke, classroom teacher at DENISE primary school, Amsterdam

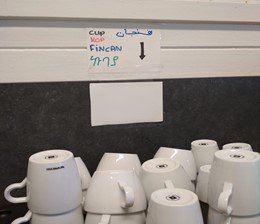

2, Label items and concepts

Take the previous idea to the next level by using multilingual labels. With young learners or with students with whom you don’t share a language, make a game of labelling whatever item they come across in the classroom or school building in as many languages as they can. Make sure to add the target language, so that the activity also serves as a learning opportunity. This activity will instantly help your students feel more at home at school.

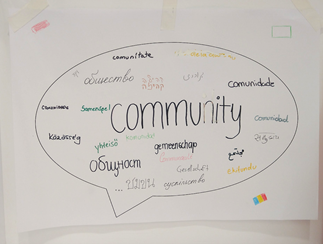

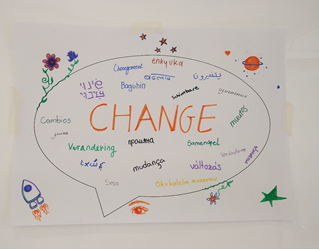

With older students, you can create multilingual posters for the main concepts when you introduce a new topic/unit. Let those students who share a language work on this task together, to make sure they find the best translation in their languages.

Let students use a translation software, if needed. Once the posters are done, hang them in your classroom for the duration of the topic/unit, as they can aid students’ understanding of the curriculum.

3, Explore your students’ language repertoire

Which languages and dialects do your students speak? How do they connect to their different languages? Which language(s) do they think, dream, read, sing and play in? Try these two simple but powerful activities with your students, and make sure you leave enough time to discuss them, as they lead to great conversations. I have seen both 6 and 17-year-olds present ‘My Body, My Languages’ with sparkling eyes, and ‘My Languages and I’ once got an 8-year-old student to spontaneously exclaim ‘I love in English!’. What else can we ask for?

Both activities are part of my Cultural and Linguistic Identity Portfolio and can be accessed for free via this link.

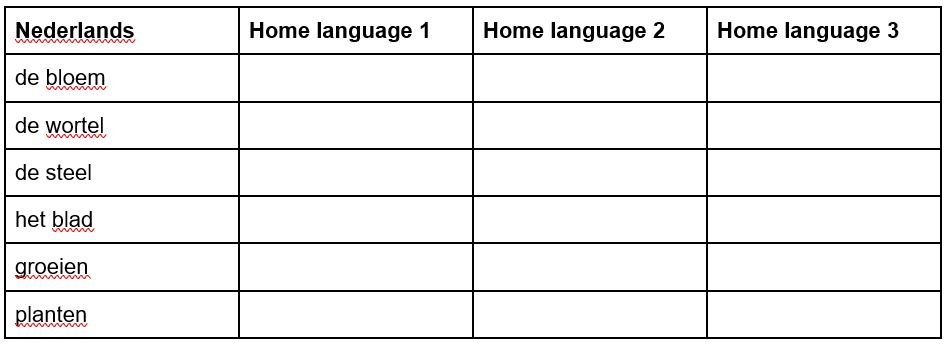

4, Send out vocabulary lists

Welcome posters alone can only take you so far. If you are aiming for equity, you need to help your multilingual students access the curriculum. That might seem daunting when you have 15 different languages in your classroom. Luckily, you have an excellent group of allies at your service: Parents!

Before each upcoming topic/unit, prepare a vocabulary list including key words and concepts that might be challenging for your students in the school language. Send this vocabulary list home, and ask parents to translate and discuss the words with their children, using their home languages. This simple first step in parent-teacher cooperation around the curriculum can go a long way, and will open the doors for other forms of cooperation. Parent-teacher cooperation is a powerful tool for strengthening your school community, and improving your students’ learning outcomes.

5, Let students prepare for assignments in the language of their choice

You will never find out what your multilingual students know, if they are only allowed to show you their knowledge in the school’s language. All you will find out is what they are able to show you. That need not be the case. When preparing for an assignment with students who can read and write independently, let them do the background work in the language of their choice. You can let them do research, prepare first drafts, or even give a presentation in the language of their choice, as long as they do the final assignment (also) in the target language. Through preparing in a language they have mastered, they will be able to show you what they really know. When writing up the final assignment, they will still be using the target language. Win-win. I have witnessed a hard-to-motivate student prepare an excellent speech this way, conducting the preparatory work in Russian and giving the speech in English. Not only was the presentation strong content-wise, but I had never heard him use such a high level of English before!

***

We all have the power to make a change, as Jim Cummins observes: “Planned change in educational systems always involves choice. Administrators and policy-makers make choices at a broad system level, school principals make choices at the level of individual schools, and teachers make choices within their classrooms.” (Cummins, 2015, p.108) Sometimes, change can be as simple as these five steps.

References:

Agirdag, O. (2017). Het straffen van meertaligheid op school: de schaamte voorbij. In O. Agirdag & E. R. Kambel (Eds.), Meertaligheid en onderwijs (pp. 44-52). Boom.

Cummins, J. (2001). Bilingual Children’s Mother Tongue: Why is it important for Education? Sprogforum, 19, 15-20. Retrieved on 14/12/2020 from http://www.lavplu.eu/central/bibliografie/cummins_eng.pdf

Cummins, J. (2009). Fundamental psychological and sociological principles underlying educational success for linguistic minority students. In Skutnabb-Kangas, T., Philipson, R., Mohanty, A. & Panda, M. (Ed.). Social justice through multilingual education, 19-35. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Cummins, J (2015). Inclusion and Language Learning: Pedagogical Principles for Integrating Students from Marginalized Groups in the Mainstream Classroom. In Bongartz, C., Rohde, A. (Ed.). Inklusion Im Englischunterricht, 95-116. Frankfurt: Peter Lang Edition.

by Mari Varsányi

______________________________________________________________________

This story is part of Multinclude Inclusion Stories about how equity is implemented in different educational environments across the globe. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Author is a consultant, trainer (human-ed) and university lecturer in the fields of intercultural and multicultural education, and former program coordinator at the Amsterdam-based superdiverse school, DENISE. You can reach Mari via https://www.human-ed.org/